Back

Whistler’s architectural evolution

Highlighting the award-winning built environment

By Steven Threndyle

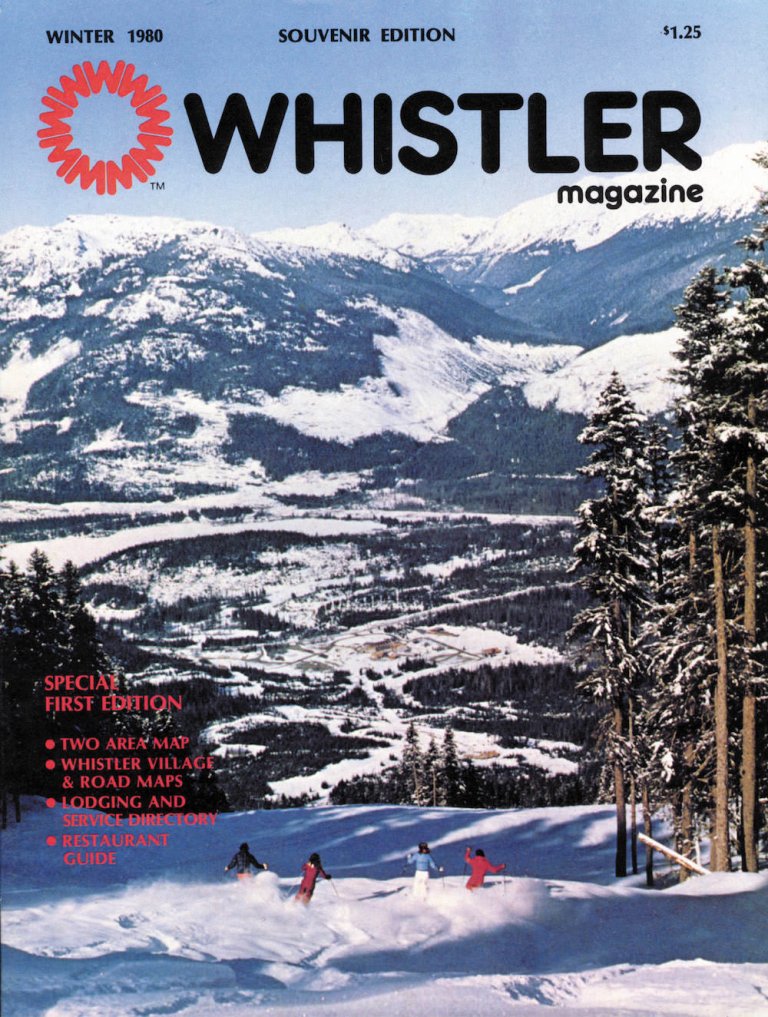

It all seems like ancient history now, but Whistler’s first decade as a ski town (from 1966 to 1976) was a rowdy, messy, and ultimately unsustainable affair. There were probably more squatter’s shacks than second homes on the decidedly challenging bluffs and forests around Alta Lake and the old gondola barn.

As Whistler began to come of age, so too did its architecture. In her 2014 book American Ski Resort: Architecture, Style, Experience, Wake Forest University architecture professor Margaret Supplee-Smith called Whistler “Canada’s great mountain experiment.”

Indeed, some of North America’s most skilled architects have left an imprint here. Arthur Erickson designed the Hearthstone Lodge, while Barry Downs (with some roofline assistance from Berkley’s Henrik Bull) created the Fairmont Chateau Whistler. MIT-trained John Perkins, who would later form the internationally-renowned Busby, Perkins & Will, had his hand in several Whistler Village lodges. Arthur Erickson’s former partner Geoffrey Massey and West Vancouver’s Bo Helliwell constructed ski cabins that battled for space with the volcanic outcrops and coastal rainforest.

Adele Weder is a contributing editor at Canadian Architect and the author of an upcoming biography on noted West Coast architect Ron Thom. Her critical take on Whistler’s built environment reveals a bit of a mixed bag. "Whistler's low-rise lodges of the 1970s are exemplary of our regional architecture: organic, beautifully simple, and complementary to the surrounding nature. I'm not keen on the brash, convoluted, faux Swiss-chalet architecture built in the decades that followed. That kind of architecture makes Whistler feel like Disneyland, but Whistler should feel like its own place.” Weder then points to some praiseworthy recent efforts that have catapulted Whistler into the ranks of award-winning architecture, namely the Whistler Public Library and the Audain Art Museum.

With that in mind, Whistler Magazine takes you on a stroll through the Village with an eye to its unique architecture. Here are some of the highlights along the way.

Whistler Village

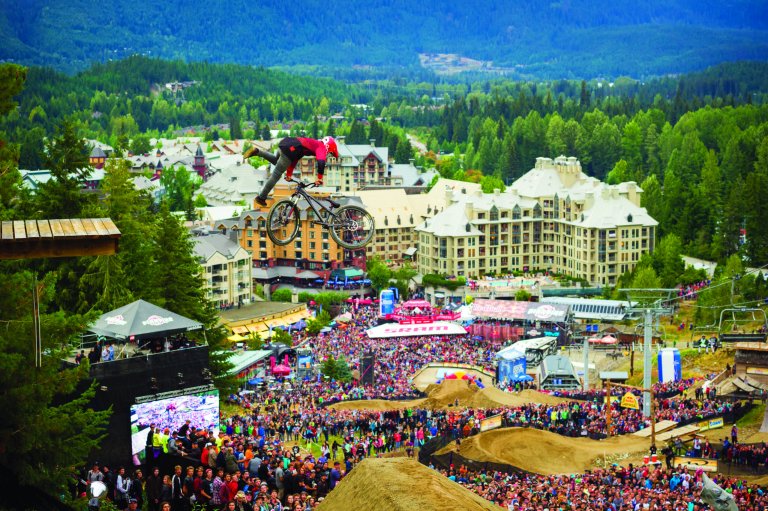

To this day, there has never been a resort built anywhere else in Canada on the scale of Whistler Village. Forward-thinking California landscape architect Eldon Beck, who designed it, believed that a pedestrian village should surprise and delight, which is why it can sometimes feel like you’re walking in circles, especially after the bars close. Three main plazas encourage lingering. Covered walkways make the Village functional even on a rainy day and allow for easy strolling and window-shopping. The pedestrian pathways double as view corridors so that skiers, snowboarders, hikers (or even dog-walkers) can gaze upon the mountains and the promise of adventure. Legendary Whistler resort planner Paul Mathews says that “the original Village still looks very good. The massing (that’s architect-speak for how a building is perceived) of low-rise three to four-storey buildings was influenced by alpine villages such as Austria’s Lech and Pete Seibert-era Vail."

Squamish Lil’wat Culture Centre

Informed by the traditional First Nations longhouse communal living space, the Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre was designed by Vancouver-based Waugh, Busby Architects in 2008. Alfred Waugh, a prominent and highly-acclaimed First Nations architect, would later create Formline Architecture, a professional firm that designs many award-winning public buildings for aboriginal and Indigenous communities throughout North America. The centre’s mandate is twofold: as a repository for thousands of artifacts and historical documents for both the Squamish and Lil’wat First Nations, and to help educate visitors from all over the world about the two Nations’ art, culture, and storytelling traditions. Extensive floor-to-ceiling windows let warm mountain light filter in and illuminate the timeless totem poles and sea-faring canoes. The building’s structure relies on honey-gold cedar posts and beams, while metal latticework adds a decorative touch to the street-facing façade.

Whistler Public Library

During the heady early years of Whistler’s growth in the ’80s and ’90s, municipal buildings and services were pretty much an afterthought since it took time to build a tax base that could support attractive and highly functional institutional buildings. One of the best examples of sustainable design principles and striking contemporary mountain architecture can be found at the Whistler Public Library. Vancouver-based Hughes Condon Marler and Associates created a bright, airy, and inviting environment that goes well beyond a library’s traditional book-lending functionality. Note how the building’s entrance segues into a community courtyard—a gathering place for special events. Much of the timberframe construction utilizes Western hemlock, an often undervalued and overlooked species. The library was the first LEED Gold-certified public library in Canada and honoured with the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia Awards in Architecture 2009—a far cry from the leaky trailer that once housed Whistler’s books.

Audain Art Museum

With its elevated “floating” walkway paralleling Fitzsimmons Creek, stark black metal cladding and light-filled, minimalist interior, the Audain Art Museum is Whistler’s most dazzling public building. Recognizing the challenges presented by extreme weather due to climate change, the museum’s main floor is elevated one storey above ground level to avoid possible flooding from nearby Fitzsimmons Creek. Designed by Vancouver-based Patkau Architects to house the private collection of Polygon Homes founder Michael Audain, this striking museum has transformed a parking lot at the edge of a floodplain into a cultural haven. Prestigious awards followed, including the Governor-General’s Medal in Architecture and the Canadian Wood Council Design Award.

Lost Lake PassivHaus

The final stop on our architectural stroll is decidedly more modest. The Lost Lake PassivHaus, located at the entrance to Lost Lake Park, housed the Austrian Olympic Committee and Austria Public Broadcasting during the 2010 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games. From the outset, the building was designed to showcase best-in-class energy efficiency. Passive House (or Passiv Haus, in German) home building technology drastically reduces energy consumption by sealing the house in an airtight building envelope. Windows, walls, vents, doorways—in short, all of the places where cold air can enter or where warm air escapes—utilize energy-saving materials. Completed in 2009, the Lost Lake PassivHaus—the first in Canada— was seen as truly revolutionary architecture. Thirteen years later, Passive House design is a feature in many new builds within the Sea to Sky corridor and across the country.

By: Whistler Magazine

GuidedBy is a community builder and part of the Glacier Media news network. This article originally appeared on a Glacier Media publication.

Recommended Spotlights

Related Stories

-

Art Galleries Whistler

Global events inspire artistic evolution

War and the pandemic have an impact on local artBy Alison TaylorThere is something about the painting Just Stop that catches...

-

Antiques, Furniture & Decor Whistler

Art in the Time of Covid

When the COVID-19 pandemic first hit, Mountain Galleries wasn’t sure what to expect. Would anyone come out to buy art? Would...

-

Art Galleries Vancouver

New study finds Canadians seek out arts to relieve stress and anxiety

A new study reveals that 71 per cent of Canadians participate in cultural experiences to reduce anxiety and stress. “Culture...

-

Arts & Entertainment Coquitlam

Dance brings rhythm to Coquitlam residents

Sponsored Content Brent Smith and Barbara Ferchuk’s dance journey began just out of high school when they enrolled as...

-

Art Galleries Vancouver

Artist Corrine Hunt surmounts adversity with humour

Tweaking the mounting of her art panels in Gastown’s Coastal Peoples Fine Arts Gallery, Corrine Hunt, Kwakwaka’wakw/Tlingit...

-

Arts & Entertainment Burnaby

Blues Fest 101: Here's how to make the most of Burnaby Blues + Roots Fest

So you wanna go to blues fest? Then do it right. If you’ve never been part of the fun that is the Burnaby Blues + Roots...

-

Art Galleries Whistler

Global events inspire artistic evolution

War and the pandemic have an impact on local artBy Alison TaylorThere is something about the painting Just Stop that catches...

-

Hiking Trail Whistler

Hiking hits new heights in Sea to Sky

Whistler is perfectly poised to make the most of the overwhelming interest to adventure outdoorsAlison TaylorJust as the first...

-

Hobbies & Leisure Whistler

Trail Mix - Things To Do & See [In & Around Whistler]

It’s a testament to Whistler, and the people who have long called this place home, that the town dreamt up as the ultimate...

-

Local Attractions Whistler

Top Summer Activities in Whistler

The snow is melting, the birds are chirping, and the flowers are starting to bloom. Sumemr has finally arrived in Whistler! If...

-

Food & Drink Abbotsford

4 Dishes to Make with Summer Peaches

Summer is the perfect time of year to experiment with different ways to use peaches. These juicy, refreshing fruits can be...

-

Home & Garden Abbotsford

How to Create a Zero-waste Household

Reducing your household waste can help the planet in many ways. You may even be able to eliminate your waste completely if...

-

Beauty & Wellness Abbotsford

7 beauty trends for summer 2021

You may be looking forward to re-entering society this summer or at least looking better during a video meeting. Beauty trends...

-

Gifts Abbotsford

Four fabulous experience gift ideas for mom this Mother’s Day

If you’re tired of giving the same old types of Mother’s Day gifts, treat your mom with an experience instead. There are many...

-

Home Furniture & Decor Abbotsford

Working from home? 4 tips for your home office setup

Working from home can be a better experience for you with the right office setup. Setting up your in-home office correctly can...

-

Whistler

Long-term State of Mind

There’s an age-old debate in Whistler about what, exactly, constitutes a “local.” Does it refer to the number of years spent...

-

Antiques, Furniture & Decor Whistler

Art in the Time of Covid

When the COVID-19 pandemic first hit, Mountain Galleries wasn’t sure what to expect. Would anyone come out to buy art? Would...

-

Local Attractions Whistler

Backcountry Bounty

Whistler is bracing for a busy season beyond the ski area boundaries. The backcountry is beckoning like never before as skiers...

-

Food & Drinks Whistler

Classic Comforts

Many of us have found comfort during these strange times with a glass of wine. Whether you venture out to one of our...

-

Canadian Whistler

Comfort Food for Uncomfortable Times

In a year in which our lives have been completely upended, it’s often the simple things that manage to bring the most...

-

Photography Whistler

Four Decades of Telling Whistler’s Stories

For a Whistler photographer, few things beat landing the coveted front cover of a ski magazine. Greg Griffith knows. SKI,...

-

Casual Dining Whistler

Safe and Cozy

Even Whistler’s finest restaurants offer a more casual vibe; such is the nature of ski resort dining where guests are often...

-

Design & Renovations Whistler

True To Its Past

The romantic and rounded form of the traditional log cabin, once a staple in Whistler’s architectural landscape, has seen its...

-

Travel Squamish

BC AdventureSmart encourages chasing waterfalls — safely

In her 15 years with the AdventureSmart program, B.C. executive director Sandra Riches said the severity of waterfall-related...

-

Jobs & Education Squamish

EDITORIAL: Squamish memories of first jobs

Summer is here and for many Squamish youngsters that means taking on their first real paid work. First jobs can be fun as...

-

Pets & Animals Squamish

Here are some dog friendly hikes you can take near Squamish

I’ve been on several hiking and camping trips with dogs over the years and they have never detracted from those experiences,...

-

Seasonal Squamish

Get artistic with Squamish summer camps

When the school year ends and it’s time to pack the kids off to summer camps, what most people think of are sports and...

-

Seasonal Squamish

Summer camps keep the kids happy and healthy

The lazy days of summer are fast approaching, and it’s time for parents to search for ways to get their kids away from their...